Public opinion on implementing the National Lung Cancer Screening Program in Korea

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in Korea and worldwide (1,2). Most of the lung cancer patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, and the recurrence rate is high even in patients who undergo curative treatments (3,4). The responses to therapy in advanced stages are generally poor and lung cancer mortality is still high (5). Therefore, primary and secondary prevention strategies are valuable in improving the survival rate of patients with lung cancer.

In Korea, survival outcomes of major cancers have dramatically improved during the past two decades, owing to the successful implementation of nationwide cancer screening programs and the development of therapeutic methods (2). However, the survival rate of lung cancer remains largely unchanged, in part due to the lack of an effective screening program and the high prevalence of advanced diseases already present at the time of the initial diagnosis.

Various efforts have been made worldwide to validate the effectiveness of lung cancer screening, mainly targeted to high-risk populations. In the United States, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) compared radiography versus low-dose CT (LDCT) in individuals with a high risk of lung cancer, defined by age (55–74 years old) and smoking history (at least 30 pack years). This trial demonstrated the survival benefit of screening using LDCT with a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality and 6.7% reduction in all-cause mortality (6). In the United Kingdom (UK), the UK Lung Cancer Screening (UKLS) pilot trial recruited individuals aged 50 to 75 years with more than a 5% risk of lung cancer for 5-year based on a risk prediction model and compared LDCT screening versus no intervention. Among 2,028 people in the LDCT arm, 42 (2.1%) participants were diagnosed with lung cancer, and 36 (85.7%) cases were detected at early stages (I or II). This trial also suggested that such a strategy was cost-effective (7). Recently, the NELSON trial from the Netherlands and Belgium have also confirmed the survival advantage of lung cancer screening using LDCT in high-risk populations defined by age (50 to 74 years) and smoking history (>15 cigarettes/day for >25 years, or >10 cigarettes/day for >30 years). The LDCT group had a reduced cumulative rate of death from lung cancer, both in men (0.76) and women (0.67) (8).

Similarly, lung cancer screening guidelines were developed in Korea targeting high-risk individuals (smoking history ≥30 pack-years and aged 55–74 years old) in 2015, and the National Lung Cancer Screening Program (NLCSP) was launched in July 2019 after the successful completion of the Korean Lung Cancer Screening demonstration project (K-LUCAS) from February 2017 to December 2018 (9).

Public agreement and active participation of eligible candidates for screening are key elements in the successful implementation of NLCSP. Therefore, this survey was conducted to comprehend people’s attitudes towards the initiation and participation in the national lung cancer screening program and to investigate the factors that could affect their opinions. Eventually, we aimed to develop strategic approaches for effective implementation of the NLCSP. We present the following article in accordance with the SURGE (The Survey Reporting Guideline) reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-865).

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Cancer Center (IRB number; NCC2020-0041). All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Survey and respondents

Data for this study were obtained from the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey (KNCSS) of 2018. KNCSS is an annual survey targeting a representative population of 4,500 individuals who are eligible for the National Cancer Screening Program for five common cancers in Korea (stomach, liver, colorectum, breast, and uterine cervix). As the screening age starts at 40 for men and 20 for women, we filtered out women who were under 40 years old to match the age groups of the survey respondents. Consequently, responses of 3,495 individuals were included in this study. Detailed methods of this survey have been previously described (10). However, to summarize, the respondents were chosen from across the country through a random sampling method, based on their age, geographic area, and gender. Survey responses were collected by a professional research agency that personally contacted the respondents. All respondents voluntarily participated in the survey (11). The 2018 survey collected detailed information regarding demographics, smoking status, and opinions on the lung cancer screening program. The response rate for this survey was 28.9%.

The following information was provided ahead of the specific question on lung cancer screening implementation: “The government announced the plan to implement national lung cancer screening program using LDCT targeting high risk population with at least 30 pack-years of smoking history. LDCT, the method of choice for lung cancer screening, has lowered the radiation exposure by 10% compared to a conventional CT. Small-sized lung cancers could be detected by LDCT, but experienced radiologists are required to diagnose the small lung cancers effectively from non-cancer lesions. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in Korea, but early detection is still challenging. Therefore, the government expected to enhance early diagnosis and survival outcomes by implementing lung cancer screening program.”

The qualitative measure of public opinion on implementing a national lung cancer screening program was collected from the question “Do you agree with launching a national lung cancer screening program that targets high-risk individuals?” A participant could choose one of the following answers: Agree, Disagree, or Do Not know. If the participants disagreed, they were asked to give their reason.

The participant preferences between the screening unit accessibility and quality of screening were measured by responses to the question on their preference for different types of screening units. Specifically, the question asked was “If you or your family were eligible for lung cancer screening, which screening unit would you prefer for undergoing screening?” A participant could choose one of the following answers: A local hospital near home, a large hospital far away from home, or no preference. Participants who responded in favor of large hospitals (referral centers) instead of small hospitals were believed to have a preference for quality over accessibility, and vice versa.

Finally, the data for public opinion on the provision of smoking cessation counselling within the national lung cancer screening program was collected from the question “What’s your opinion on providing mandatory smoking cessation counselling to current smokers who are participating in lung cancer screening?” A participant could choose one of the following answers: Must provide smoking cessation counselling, providing information regarding smoking cessation is enough, provision of smoking cessation counselling is not necessary, or no opinion.

The questions regarding lung cancer screening were developed by a group of experts and a small pilot test was performed to check the error and feasibility of the questions.

Eligibility criteria for Korean National Lung Cancer Screening

The eligibility criteria for lung cancer screening were defined based on smoking history and age in order to select high-risk populations (9). Current or former smokers (who quit within the past 15 years) aged between 55 and 74 years and with at least 30 pack-years of smoking history were considered eligible for screening. Smoking history had to be cross validated on a self-reported questionnaire for the national health screening program or the public smoking cessation program supported by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) within the past 2 years.

Statistical analysis

The association between lung cancer screening eligibility and opinion on implementing a national lung cancer screening program by smoking status was evaluated through Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Binary logistic regression was also used to identify factors that were associated with the public’s opinion on implementing a national lung cancer screening program (Agree or Disagree). Individuals with no opinion on implementation were excluded from the logistic analysis.

Chi-square test was used to analyze the association between public preferences on screening unit accessibility and quality of screening. Participant characteristics and the association between screening eligibility and public opinion on provision of smoking counselling within the lung cancer screening program were also evaluated through chi-square test. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software version 14 (Stata Corp. L.P., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

General characteristics of survey respondents

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the survey respondents based on their smoking status. Among 3,495 participants, 2,378 (68.0%) were never smokers and 1,117 (32.0%) had a smoking history. There were 205 people (5.9%) eligible for lung cancer screening with 148 current smokers and 57 former smokers. The eligible population was mostly male (N=201, 98.1%) and were living with their spouses (N=193, 94.2%). Compared to the non-eligible group, the eligible group generally had a lower household income (<3.0 million KRW per month, 22.2% vs. 41.0%), lower education level (undergraduate or higher, 35.5% vs. 16.6%), and a lower number had urban residency (87.9% vs. 79.5%). Also, a lower number of respondents in the eligible group considered their health status to be good (66.6% vs. 59.5%), though more of them responded in the affirmative to having regular health checkups (43.5% vs. 54.6%).

Full table

Public opinion on implementing the national lung cancer screening program by smoking status and eligibility

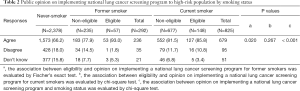

We asked the public opinion about implementing the national lung cancer screening program in high-risk populations based on age and smoking status (Table 2). A total of 2,488 (71.2%) respondents agreed with implementing the national lung cancer screening program. However, the proportion of people who agreed was not consistent among the different subgroups based on smoking status. In never-smokers, 66.2% (1,573 out of 2,378) agreed with initiating the screening program, but the percentages were higher in former and current smokers with 80.8% (236 out of 292) and 82.3% (679 out of 825), respectively, showing statistically significant difference (P<0.001). Within former smokers, the percentage of agreement was higher in the eligible group (93.0% vs. 77.9%) and the opinion for implementing lung cancer screening was significantly different based on their eligibility (P=0.020). Among current smokers, however, the percentages of people who agreed with the screening program were similar in both eligible and non-eligible groups (85.8% vs. 81.5%), and the differences of their opinions were not statistically significant (P=0.267).

Full table

In total, 558 respondents (16.0%) disagreed with implementing the national lung cancer screening program. The majority were never smokers (428 out of 558, 76.7%), and even within the former or current smokers, most were non-eligible for the screening program [former smokers, 34 out of 35 (97.1%); current smokers, 79 out of 95 (83.2%)] (Table 2). Among the reasons for disagreeing with the screening program, the most frequent response was “Lung cancer screening should also be provided for low-risk populations” (47.1%) (Figure 1). Other common responses included “Lung cancer screening does not prevent lung cancer” (19.4%), followed by “Personally not eligible for lung cancer screening” (18.5%), and “Government funds should not be spent on lung cancer screening. Smoking is a private decision” (15.1%).

Demographic factors associated with public opinions on implementing the national lung cancer screening program

It was found through univariate analysis that the factors associated with agreement to implementing the lung cancer screening program including the gender being male, presence of private health insurance, regular health checkup experience, smoking history, and screening eligibility were significantly associated (Table 3). Furthermore, among these factors, presence of private health insurance [odds ratio (OR) 1.36, 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.04–1.78], regular health checkup (OR 2.10, 95% CI, 1.72–2.57), and history of smoking (former smokers, OR 1.66, 95% CI, 1.09–2.55; current smokers, OR 1.97, 95% CI, 1.45–2.67) were also significantly associated with agreement to implementing the lung cancer screening program in multivariate analysis (Table 3).

Full table

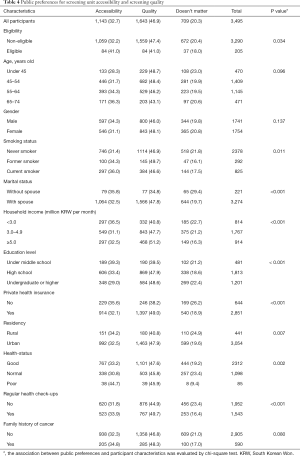

Preference of screening units for lung cancer screening

The preference for the screening units was also surveyed (Table 4). The questionnaire asked whether respondents preferred accessibility or quality as the basis for choosing the medical facility for screening. The preference for quality was generally higher than accessibility (46.9% vs. 31.9%). However, the preferences differed among various subgroups. In the eligible group, a higher portion of respondents preferred accessibility compared to the non-eligible group (41.0% vs. 32.2%). Conversely, quality was preferred more by non-eligible people as compared to eligible respondents (47.4% vs. 41.0%). Preference for accessibility was higher in respondents with lower household income (<3.0 million KRW, 39.3% versus ≥5.0 million KRW, 32.5%) while the preference for quality was higher in people with higher household income (<3.0 million KRW, 40.8% versus ≥5.0 million KRW, 51.2%). The pattern was similar to that based on education level, as respondents with lower education levels showed higher preference for accessibility (under middle school, 39.3% versus undergraduate or higher, 29.0%) while people with higher education levels showed higher preference for quality (under middle school, 39.5% versus undergraduate or higher, 48.6%).

Full table

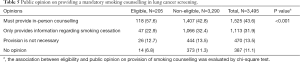

Opinion on providing mandatory smoking counselling in lung cancer screening program

Among the 3,495 respondents, 1,525 (43.6%) required that a mandatory in-person smoking cessation counselling should be provided and 1,113 (31.9%) responded that providing information regarding smoking cessation should be given (Table 5). Only 470 (13.5%) people thought smoking cessation counselling is not necessary. The majority (57.6%) of population that were eligible for screening responded affirmative for providing mandatory in-person counselling. The opinions on providing these services significantly differed between the subgroups based on screening eligibility (P<0.001) (Table 5).

Full table

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively reviewed the people’s attitudes towards implementing the NLCSP through a survey targeting a large representative adult population. As the NLCSP is reimbursed by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) of Korea, a nationwide social health insurance system with compulsory subscription, it is imperative to obtain widespread agreement of the general population for implementing a program confined to the high-risk population. Among the survey respondents, the majority were never smokers (2,378 out of 3,495, 68.0%) and the eligible group consisted of only 205 people (5.9%). Nevertheless, a high portion of respondents (71.2%) agreed with implementing NLCSP to the high-risk population. The proportion of agreement, however, was significantly different among smoking status, as the agreement rate was higher in former and current smokers compared to never-smokers. And even within former smokers, eligible people were more amenable to the screening program (Table 2). Furthermore, multivariate analysis of the demographic factors related to the opinion on NLCSP showed that smoking history, both former and current, were significantly associated with agreement (Table 3). These data imply that people with higher chances of being a potential candidate for lung cancer screening tended to be more affirmative towards implementing lung cancer screening in the high-risk population.

Intriguingly, 47.1% of the people who disagreed with implementing NLCSP responded that the screening should also be provided to the low-risk population as well. Also, 19.4% responded that lung cancer screening does not prevent lung cancer (Figure 1). The eligibility criteria of the NLCSP were established based on the firm evidence of survival benefit when targeting the high-risk population for lung cancer screening (12). Currently, there is little evidence that lung cancer screening leads to survival benefit in lower risk groups. Besides, there are potential harms including unnecessary imaging and procedures for false positive lesions, as well as psychological harm due to anxiety of the screening process (9). Therefore, it would be essential to clarify the potential harms and benefits of lung cancer screening to the public.

Recently, a survey among lung cancer specialists in Korea reported that 77.6% of the respondents agreed with the LDCT-based strategy of the NLCSP (13). However, there were also concerns about high false positive results, quality control of CT devices and radiologic interpretations, and limited access to screening facilities. Strategies to minimize the negative effects of these concerns would be crucial for implementing the NLCSP successfully.

The demographic characteristics of our cohort indicate that the high-risk population, representing individuals with a heavy smoking history, are mostly men and tend to have a lower household income and lower education level. This is in line with data from other countries, reporting that smoking rates are higher among people with lower socioeconomic status (14,15). However, previous studies with the KNSCC have shown that intentions to undergo lung cancer screening in high-risk populations were not significantly associated with household income or education level (16,17). Therefore, it is important to provide low-barrier screening opportunities so as not to exclude those with disadvantaged socioeconomic status.

The key issues with implementing the nationwide lung cancer screening program are promoting the participation of the high-risk population in the screening program and minimizing the risk of unnecessary examinations by exercising screening quality control.

Accessibility of screening facilities is an important factor to increase the participation rate among high-risk individuals in a population-based screening program. In Korea, the abundance and widespread distribution of CT scanners along with several radiology specialists enable even small to medium-sized hospitals that are easily accessible to operate the screening program (18). However, the screening units do vary in their capacity and expertise. Guidelines suggest that lung cancer screening units require high-quality CT scanners with quality control, extensive thoracic oncology activity, and multidisciplinary experts for the management of suspicious findings in order to provide effective screening (19,20). These are necessary to minimize the harms associated with false positive lesions such as unnecessary repetitive radiation exposures, psychological harms, and surgery for benign lesions (21,22). Based on this information, we analyzed whether the survey respondents prioritized accessibility or quality of the screening unit. We found that most of participants had a higher preference for quality than accessibility (Table 4). As the accessibility of lung cancer screening is still an important issue, this suggests that an infrastructure of sufficient qualified medical institutions could be a key factor in implementing the NLCSP successfully.

Quality control is another important issue in this nationwide screening program. In order to standardize the screening process and consistently maintain the quality for accuracy among the screening units, there are several requirements that need to be met. First, CT must be a multichannel scanner with a minimum of 16 channels, and the results must be evaluated in accordance with the lung imaging reporting and data system (Lung-RADS) suggested by the American College of Radiology (23). Second, radiologists must complete relevant education and be qualified to conduct the screening. Together, these essential prerequisites can assure the quality of the LDCT-based screening. Besides these standardized setting for mass screening, a centralized monitoring system would be required for keeping screening quality by using indicators including participation rate among high-risk population, screening positive rate, and smoking cessation rate after screening.

Continued smoking has a causal relationship with adverse outcomes in cancer. It is associated with higher mortality, risk of disease progression, and the risk of other tobacco-related malignancies (24). For these reasons, screening itself cannot be considered as an alternative to smoking cessation (25). Regarding the goal of screening which is to enhance the survival outcome of lung cancer, counseling for smoking cessation is a pivotal strategy that must be integrated with routine examinations (26,27). The NLCSP also provides counselling for smoking cessation, and majority of the respondents (75.5%) were generally affirmative towards this. Based on the pilot study of the NLCSP (K-LUCAS), counselling had a positive effect on the participants’ will to quit smoking (9). Currently, there is little data showing the feasibility and efficacy of smoking cessation interventions in the context of lung cancer screening (25). Cumulative data from the NLCSP which provides mandatory smoking cessation counselling could prove to be significant evidence when the long-term outcomes of the population-based lung cancer screening program come out to be successful.

Innovative artificial intelligence (AI) systems may greatly enhance the efficiency of radiologic evaluation. In the pilot trial for the Korean Lung Cancer Screening Program (K-LUCAS), a network-based diagnosis supporting system using computer-aided detection was adopted (9). However, this has not yet been integrated into the nationwide screening program in Korea. There are studies that have validated an increase in positive predictive values and a reduction in false-positive rates for lung cancer screening when such computer-aided diagnostic algorithms are used (28). Therefore, we foresee that AI-aided CT diagnosis would greatly enhance the quality and speed of the nationwide screening program, if properly validated.

This study has several limitations. First, despite the large number of survey respondents included in this study, the portion of eligible population for lung cancer screening was relatively small. Furthermore, individuals that fulfill the eligible criteria for lung cancer screening were reported to have lower adherence to general medical checkup guidelines (29). Therefore, opinions from the eligible group might have been underrepresented in this study. Second, there might be both interviewer and response biases when the respondents were questioned about their opinions on agreement with the lung cancer screening program, healthcare-related habits, or socioeconomic status. Under-reporting of smoking habits in Asian women is a major concern especially with regards to smoking history (30).

Several pivotal studies have been conducted in different countries that have also commonly targeted high-risk individuals for lung cancer screening. However, the criteria used to define a high-risk individual vary from one study to another (6-8). This is primarily due to differences in population, epidemiology, smoking status, economic status, and healthcare systems between countries. Nonetheless, smoking status and age have been common factors used in all of these studies. Further, while it seems difficult at present to arrive at a global consensus on the selection criteria for high-risk individuals, cumulative evidence might provide insights for developing a risk prediction model that can help in reducing lung cancer mortality by more efficiently identifying high-risk individuals. This model may not only consider smoking history but also other risk factors such as family history, chronic lung disease, and carcinogen exposures in working sites.

As clinical trials performed worldwide have validated the mortality reduction through lung cancer screening with LDCT in high-risk populations, the successful implementation of the NLCSP is important in enhancing the survival outcome of lung cancer in Korea. We speculate that our data would be a valuable resource in building appropriate strategies and policies to maximize the benefits of NLCSP. Furthermore, it could also be a good reference for other countries that are attempting to administer analogous lung cancer screening programs.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (1720310) and a research grant from National Cancer Center, Republic of Korea (1610430).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-865

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-865

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-865

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-865). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Cancer Center (IRB number; NCC2020-0041). All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, et al. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2015. Cancer Res Treat 2018;50:303-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meza R, Meernik C, Jeon J, et al. Lung cancer incidence trends by gender, race and histology in the United States, 1973-2010. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121323 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torre LA, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Lung Cancer Statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016;893:1-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walters S, Maringe C, Coleman MP, et al. Lung cancer survival and stage at diagnosis in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK: a population-based study, 2004-2007. Thorax 2013;68:551-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395-409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Field JK, Duffy SW, Baldwin DR, et al. UK Lung Cancer RCT Pilot Screening Trial: baseline findings from the screening arm provide evidence for the potential implementation of lung cancer screening. Thorax 2016;71:161-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med 2020;382:503-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee J, Lim J, Kim Y, et al. Development of Protocol for Korean Lung Cancer Screening Project (K-LUCAS) to Evaluate Effectiveness and Feasibility to Implement National Cancer Screening Program. Cancer Res Treat 2019;51:1285-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suh M, Choi KS, Park B, et al. Trends in Cancer Screening Rates among Korean Men and Women: Results of the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey, 2004-2013. Cancer Res Treat 2016;48:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong S, Lee YY, Lee J, et al. Trends in Cancer Screening Rates among Korean Men and Women: Results of the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey, 2004-2018. Cancer Res Treat 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jang SH, Sheen S, Kim HY, et al. The Korean guideline for lung cancer screening. J Korean Med Assoc 2015;58:291-301. [Crossref]

- Shin DW, Chun S, Kim YI, et al. A national survey of lung cancer specialists' views on low-dose CT screening for lung cancer in Korea. PLoS One 2018;13:e0192626 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Geurts JJ, et al. Educational differences in smoking: international comparison. BMJ 2000;320:1102-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, et al. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1248:107-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bui NC, Lee YY, Suh M, et al. Beliefs and Intentions to Undergo Lung Cancer Screening among Korean Males. Cancer Res Treat 2018;50:1096-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nhung BC, Lee YY, Yoon H, et al. Intentions to Undergo Lung Cancer Screening among Korean Men. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015;16:6293-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Korean Statistical Information Service [Internet]. Daejeon (Korea): Statistics Korea. c2020 - [cited 2020 April 2]. Available online: https://kosis.kr/eng/index/index.do

- Postmus PE, Kerr KM, Oudkerk M, et al. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2017;28:iv1-iv21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pedersen JH, Rzyman W, Veronesi G, et al. Recommendations from the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS) regarding computed tomography screening for lung cancer in Europe. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;51:411-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oudkerk M, Devaraj A, Vliegenthart R, et al. European position statement on lung cancer screening. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:e754-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mulshine JL, D'Amico TA. Issues with implementing a high-quality lung cancer screening program. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:352-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JW, Kim HY, Goo JM, et al. Radiological Report of Pilot Study for the Korean Lung Cancer Screening (K-LUCAS) Project: Feasibility of Implementing Lung Imaging Reporting and Data System. Korean J Radiol 2018;19:803-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Reports of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), 2014.

- Minnix JA, Karam-Hage M, Blalock JA, et al. The importance of incorporating smoking cessation into lung cancer screening. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2018;7:272-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Godtfredsen NS, Prescott E, Osler M. Effect of smoking reduction on lung cancer risk. JAMA 2005;294:1505-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tindle HA, Stevenson Duncan M, Greevy RA, et al. Lifetime Smoking History and Risk of Lung Cancer: Results From the Framingham Heart Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018;110:1201-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang P, Park S, Yan R, et al. Added Value of Computer-aided CT Image Features for Early Lung Cancer Diagnosis with Small Pulmonary Nodules: A Matched Case-Control Study. Radiology 2018;286:286-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim EY, Shim YS, Kim YS, et al. Adherence to general medical checkup and cancer screening guidelines according to self-reported smoking status: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2010-2012. PLoS One 2019;14:e0224224 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jung-Choi KH, Khang YH, Cho HJ. Hidden female smokers in Asia: a comparison of self-reported with cotinine-verified smoking prevalence rates in representative national data from an Asian population. Tob Control 2012;21:536-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]