Approach to offering remote support to mesothelioma patients: the mesothelioma survivor project

Introduction

Mesothelioma is a cancer that primarily affects the pleura and peritoneum and is usually caused by exposure to asbestos. The number of individuals diagnosed with mesothelioma is increasing world-wide, particularly in developing countries where the use of asbestos is poorly regulated (1). In spite of advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical approaches, mesothelioma remains resistant to treatment. According to the International Mesothelioma Interest group, overall survival has not improved, whereas median survival times vary from one month to eighteen months.

Few patients remain asymptomatic or with minimal symptoms for extended periods of time, and fewer live three years or more. Mesothelioma is often associated with unwieldy, intractable symptoms, particularly in experiencing pain and difficulty breathing. Poor prognoses have been reported for those diagnosed with sarcomatoid over epithelioid histology, or with advanced disease, poor performance status, pain and loss of appetite.

Mesothelioma has a number of emotional consequences. A study conducted by the British Lung Foundation (BLF) reported significant impairment of emotional function and/or emotional states in patients with mesothelioma as well as in their family members (2). The BLF’s study further reported a more positive response amongst patients versus caregivers in regards to supportive treatment to their emotional functioning. However, authors did not provide a definition for significantly impaired emotional functioning, thus opacifying the results of such support.

The physical, psychological, social, and financial burdens of patients being treated for various types of peritoneal cancer are often accompanied by exorbitant travel, lodging, and medical treatment expenses that can become overwhelming and burdensome to patients and their families. These financial expenditures can become even larger when treatments are postponed or canceled due to adverse effects of disease or treatment (2,3).

Recent psychological studies have demonstrated health benefits in cancer patients when sharing their illness experiences through online blogs. Blogging creates a survivor identity and facilitates a social support network for patients. Further, studies suggest that expressive writing increases self-management of chronic pain and lowers depressive symptoms (4,5).

The Mesothelioma Survivor Project is a virtual platform designed to offer emotional support to participants by allowing them to ask questions and share thoughts they may not feel comfortable voicing in a traditional support group.

Methods

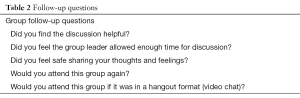

The platform for the support group was remote, consisting of both online and telephone domains. Each participant received an email a week prior to support sessions with an access code to the online and phone conference systems. Participants would then utilize the online and phone systems during sessions, which were held once a week during evenings for a total of six weeks. These confidential sessions were guided (by a team of healthcare professionals consisting of: a social worker, nurse, and a member of the patients support team from the Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation) and available only to those affected by mesothelioma—confidentiality was kept to best facilitate open dialogue. Discussion questions were designed for this unique patient population—aimed at addressing their specific quality of life (QOL) concerns (Table 1). The platform facilitated anonymity should a patient have wished to remain so. Follow-up information and session summaries were provided after support meetings online. Additionally, each participant was provided a survey to evaluate the facilitators and overall effectiveness of the group (Table 2).

Full table

Full table

Results

Patients expressed satisfaction via online surveys after each session. Using a 0–5 Likert Scale, consistent attendees reported support groups as very helpful (2). Irregular attendees had mixed feelings ranging from extremely helpful (5) to neutral (3). Eighty per cent of attendees participated in support groups prior to ours. Of the patients surveyed, more than 50 per cent said they would participate in a video chat formatted support group.

Discussion

Active participation in a guided support group allowed participants to share feelings and concerns about diagnoses without feeling judged by their peers or healthcare providers. In the process, participants received the emotional, mental, and post-active treatment support they required to facilitate the transition to follow-up care.

The online portion of the platform was particularly helpful in assuaging common negative concerns like fear of healthcare provider judgment, confidentiality, self-editing, emotional backlash from loved ones, and disapproval of lifestyle post-active treatment. Analysis of support session dialogue allowed facilitators to gauge information available to patients as well as provide information about life after active treatment. Online space (on our blogspace) gave participants a place to provide more communicative responses outside the main dialogue of support sessions.

Acknowledgements

All participants were asked to participate in these guided support groups by the Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation patient support team. Supported in part by gifts to the Columbia Mesothelioma Center from, The Vivian and Seymour Milstein Family, The Gershwin Family, and The Simmions Mesothelioma Foundation.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Carbone M, Ly BH, Dodson RF, et al. Malignant mesothelioma: facts, myths, and hypotheses. J Cell Physiol 2012;227:44-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nowak AK, Stockler MR, Byrne MJ. Assessing quality of life during chemotherapy for pleural mesothelioma: feasibility, validity, and results of using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire and Lung Cancer Module. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3172-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kazan-Allen L. Asbestos and mesothelioma: worldwide trends. Lung Cancer 2005;49:S3-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gortner EM, Rude SS, Pennebaker JW. Benefits of expressive writing in lowering rumination and depressive symptoms. Behav Ther 2006;37:292-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morgan NP, Graves KD, Poggi EA, et al. Implementing an expressive writing study in a cancer clinic. Oncologist 2008;13:196-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]