Tobacco and electronic nicotine delivery systems regulation

Introduction—the FCTC and big tobacco

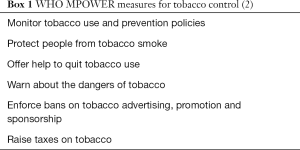

The control of tobacco cigarette consumption around the world varies considerably despite the development of the FCTC (1) and the six MPOWER (2) measures (Box 1) of the WHO. However, even with patchy implementation, there is a recognized, global, unified effort to control tobacco based on multiple strategies. The FCTC has a number of fundamental components to reduce the demand and the supply of tobacco (3). Measures to reduce demand for tobacco include elevations in price and tax, bans on smoking to reduce smoke exposure, regulation of cigarette content, plain packaging and warning labels, restriction on advertising and programs to help smokers quit (3). Measures to restrict supply include legislation against illicit tobacco, control of tobacco sales to the underaged and the development of economic alternatives for tobacco growers (3). Whether or not these measures take effect often depend very closely on the strength and determination of government and several examples make this clear. Plain packaging of cigarettes, covered by Article 11 of the FCTC (3), first eventuated in Australia (4) but survives only after strong political commitment and defence against gargantuan litigation attacks by the tobacco industry. A look at the timeline of the introduction of plain packaging in Australia highlights the difficulties faced and the unswerving governmental support required to ensure its success. The legislation was announced in April 2010, the Act was passed in November 2011 and came into effect in December 2012 (5). Very quickly, the Australian government faced three major challenges, even before the legislation was enacted. The tobacco industry challenged the legislation domestically and lost in a decision handed down by Australia’s High Court in October 2012 (6). A quartet of countries (Cuba, Dominican Republic, Honduras and Indonesia) challenged the legislation before the World Trade Organisation, eventually losing in a decision released in mid-2018 (7). Phillip Morris Asia made a claim in separate litigation that Australia was guilty of breaching a trade agreement with Hong Kong (5), a claim overturned by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in December 2017 (8). The FCTC, in particular Article 5.3 (3), which prioritizes public health policy over the commercial interest of the tobacco industry, featured in the defence in both the Australian High Court and the Phillip Morris Asia decisions. The burden of litigation continues with an appeal against the WTO made by Honduras and the Dominican Republic (9) likely to continue into the future. In contrast, when governments weaken, the tobacco industry can take opportunities to force the overturn of legislation and the diminution of effective tobacco control. Following federal elections in Austria in 2017, the incoming coalition proposed the overturn of 2015 legislation for widespread shisha and vaping bans as well as smoking bans in all hospitality venues (10) even in the facing of rising smoking rates and relatively poor performance compared with other European countries (11). This decision contradicted the anti-smoking views previously held by prior governments and led to a public outcry and petition, which has yet to be addressed by parliament (12). In the face of relatively high developed world smoking rates (13), Japan continues to struggle with tobacco control measures hindered at least in part by extensive government ownership of Japan Tobacco (14), a major transnational tobacco corporation. When implemented, FCTC tobacco control policies are effective, made evident by lower smoking rates and higher quit rates in an analysis of European Member States comparing data between 2007 and 2014 (15). The global regulation of tobacco differs in scope, depth and impact from that of e-cigarettes even as sales of the latter continue to rise; there are 181 countries that are party to FCTC at the time of writing (3) whereas many countries lack regulation tailored to e-cigarettes and many lack any regulation at all.

Regulation and control—tobacco cigarettes

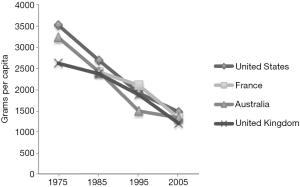

The regulation of tobacco cigarette control has developed globally over the last 50–60 years as the efforts of international and national organisations have come together. The publication of powerful epidemiological analyses in the early to mid-20th century (16-19) culminated in the landmark United States Surgeon General’s report on Smoking and Health in 1964 (20). This was a pivotal time for tobacco control as it was after the mid-1960s, at least in the United States, that per capita cigarette consumption began to decline and a range of tobacco control measures (advertising bans, increases in cigarette taxes, greater availability of nicotine replacement, greater government regulatory power) came into place (21). Data on tobacco consumption from a number of developed countries show convincing declines over the 30 years from 1975 (22) (Figure 1). The FCTC, the first treaty negotiated under the WHO, came into force in 2005 (23) and provides a single, internationally backed approach to tobacco control. The relationship between the FCTC and the WHO, not as clear as that of project and sponsor, is analysed in a recent publication that identifies the independent legal status of the FCTC (and its governing body, the Conference of the Parties) as a significant driving force (24). The MPOWER measures (2) (Box 1) support specific components of the FCTC (24) and identify some of the most effective of the tobacco control strategies. As a result, tobacco cigarette consumption has declined in most developed countries. The tobacco cigarette “epidemic” in these countries, with the rise and fall in consumption followed (after 20 years by the rise and fall of smoking related mortality (25), attests to the importance of ridding the rest of the world of this affliction. The current paradigm of tobacco control has over half a century of evidence, an international treaty, associated reductions in tobacco cigarette consumption and a structure that helps government withstand the legislative attacks of the tobacco industry. More recent and less conventional tobacco industry efforts to sanitize their dealings, such as the PMI Foundation for a Smoke-Free World (26), have received robust and prominent criticism. A number of prominent scholars in the field have voiced scepticism about the true intent of Foundation, “to improve global health by ending smoking in this generation”, in papers published in the Lancet and in JAMA among others. Daube and colleagues, in a Lancet commentary, throw doubt upon the credibility of this claim, noting that PMI continues to market tobacco cigarettes aggressively in low and middle-income countries (27). In a JAMA Viewpoint, the authors question the Foundation’s true impact: unless PMI uses its “power to…cease production of cigarettes…terminate marketing and advertising…stop litigating…”, the Foundation “only diverts attention” and acts to distract from the real needs of tobacco control (28). And by encouraging the maintenance of nicotine addiction through e-cigarettes and heat-not-burn products, by continuing to profit from the sales, the Foundation is no more than “a platform for its sponsor’s latest products” (29).

How the regulation of ENDS differs from tobacco cigarettes

At the time of writing, the regulation of ENDS around the world differs in many ways from tobacco cigarettes, more like an emerging consumer product than of a health-care intervention and no WHO treaty exists for ENDS control. Regulation of ENDS varies enormously between countries. In Australia nicotine e-cigarettes are against the law, with few exceptions (30). In the UK, e-cigarettes are widely available and supported for smoking cessation by Public Health England (31). In the United States, concerns about rapid rises in the use of e-cigarettes by non-smoking adolescents (32) and a possible gateway effect towards tobacco cigarette smoking (33,34) have led the FDA to take a number of steps including warnings to manufacturers on sales to minors and a specific focus on the appeal of the Juul device (35) and to restrict the flavouring of ENDS nicotine liquid (34). A review of global e-cigarette regulation from 2016 identified, through general and targeted web searches, 68 countries with a range of regulatory standards (36). There have been some attempts to unify ENDS regulation by the FCTC, with a 2014 report that recommends regulatory options that include health claims, public vaping, advertising and marketing, protection from commercial interests [Article 5.3 of the FCTC (3)], health warnings and sales to minors (37). This followed a report from the WHO Tobacco Free Initiative (linked to but not part of the FCTC) that made a number of ENDS policy recommendations towards optimizing any potential public health benefit of the devices (38). As of 2016 (36), ENDS regulations currently in place around the world include banning in enclosed public spaces, limitation of advertising, regulation of ingredients, child-safety standards and a number of other issues, summarised in Table 1. The distribution of these measures is not uniform; compared with the number of countries that are party to the FCTC, the number of countries with even partial ENDS regulation is small. Effective future regulation and control of ENDS will need clear recognition of the different potential users (refractory smokers who may benefit from short-term use versus young non-smokers who may develop nicotine addiction) and will depend on the ability of the health and regulatory communities to withstand the power of the transnational tobacco corporations.

Full table

Effective ENDS regulation has been hampered by industry-led claims of harm reduction. Combustible cigarettes are unequivocally harmful with no purported health benefit, allowing a clear legislative framework to emerge. Tobacco smoking kills more than 7 million people per year (39), dwarfing, for example deaths from tuberculosis (1.6 M/year) (40), motor vehicles (1.3 M/year) (41), HIV AIDS (0.94 M/year) (42) and malaria (0.5 M/year) (43). It is difficult to envisage any consumer product that is more harmful; the statement that ENDS are ‘95% less harmful than cigarettes’ therefore requires significant qualification. Tobacco industry versions of ‘harm reduction’ such as low tar, filters etc., have been exposed as fraudulent, mendacious propaganda (44). Sparse high-quality data exist supporting ENDS in helping people quit combustible cigarettes, at the time of writing there is only a single positive randomized-controlled trial in 886 subjects (45). Although ENDS have many worrying adverse effects and are clearly addictive especially to children, ENDS manufacturers position them as ‘harm reduction’ agents.

The impact of industry infiltration on tobacco control

The priority of big tobacco is to maintain market share and profits. Big tobacco has a long history of interference with tobacco control using a broad range of tactics, including political lobbying, financing research, attempting to subvert regulatory and policy machinery and public relations campaigns (46,47). Phillip Morris International, one of the world’s largest transnational tobacco companies, employs over 600 corporate affairs executives, one of the world’s biggest corporate lobbying arms, to achieve this (48) and is the sole funder of the controversial Foundation for a Smoke-Free World (49). In parallel to the above strategies, allegations and evidence of direct involvement in smuggling and links to organised crime have emerged (46,50-57). The global rally of nations under the FCTC treaty is a major concern to tobacco companies. Leaked documents illustrate how Philip Morris International has targeted the treaty on multiple levels (58). A major aim is to ensure tobacco control remains within scope of international trade deals, allowing a mechanism to mount legal campaigns against regulation (1). This is achieved in part by persuading delegations to include more representation from trade, finance and agriculture ministries, who may prioritise tobacco revenues over health concerns, watering-down representation from health ministries and generally trying to ensure policy is influenced by commercial rather than health concerns.

These diverse tactics are exemplified by the attempts to derail plain packaging laws. These laws aimed to ban the use of logos, brand imagery, symbols, other images, colours and promotional text on tobacco products and packaging and to standardise the appearance of packs, across all brands, including colour, shape and size (59).

From as early as the 1970s, industry recognized the importance of packaging:

“Under conditions of total [advertising] ban, pack designs and the brand house and company ‘livery’ have enormous importance in reminding and reassuring the smokers. Therefore, the most effective symbols, designs, colour schemes, graphics and other brand identifiers should be carefully researched so as to find out which best convey the elements of goodwill and image. An objective should be to enable packs, by themselves, to convey the total product message”. BAT Future Communication Restrictions in Advertising Guidelines 1979 (60).

The idea for plain packaging regulation was developed in Canada and New Zealand (61). The industry quickly recognised the threat and agreed to cooperate to fight against it. Eight international tobacco companies set up the ‘Plain Pack Group’ to spearhead a coordinated, global strategy against plain packaging in 1993 (61). The industry successfully stalled plain packaging laws in Canada and Australia in the 1990s using false threats of legal action, even though they had already received advice that there was no basis for legal challenge (61).

When plain packaging was again recommended in Australia in 2008 (62), the tobacco industry orchestrated a massive campaign to turn opinion through media and internet advertising, public relations campaigns, ‘astroturf’ front groups (that is an illusory “grass roots” supportive campaign that does not really exist) (63) and direct and indirect political lobbying. The industry predicted a range of ‘catastrophic’ outcomes, none of which eventuated (64,65). Once the laws were enacted, tobacco companies brought three legal challenges: (I) a constitutional challenge in the High Court of Australia brought by British American Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco, Japan Tobacco and Philip Morris; (II) an investment treaty challenge by Philip Morris Asia under a 1993 Hong Kong—Australia trade agreement; (III) World Trade Organisation disputes brought by Ukraine, Honduras, the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Indonesia, financially supported by Philip Morris and British American Tobacco, claiming plain packaging rules infringed trademarks and constituted an illegal barrier to trade (59,66). By 2018 all three challenges had been dismissed, a clear rebuttal of the tobacco industry’s arguments and validation of Australia’s plain packaging laws. Cynically, the tobacco industry knew its legal arguments were flawed and unlikely to win (61), yet pressed ahead simply to slow-down the uptake of this effective tobacco control measure by other countries, so-called “regulatory chill” (67). As a leaked 2014 Philip Morris document states “Roadblocks are as important as solutions.” (48). Despite the failure of legal challenges against Australia, tobacco companies have continued with legal challenges to plain packaging laws in other countries, with their cases dismissed in France, Norway, and the UK (68). Importantly, the court documents from the UK will be made publicly available to assist other countries to stand up to the tobacco industry (69).

The tobacco industry also seeks to ‘divide-and-conquer’ the tobacco control movement. PM’s Project Sunrise ran for a decade from 1995 with the aim to establish relationships with “moderate” tobacco control individuals and organisations and marginalise others, exploiting existing differences of opinion within tobacco control to “exacerbate conflicts” (70,71). Project Sunrise also aimed to reposition the industry as ‘responsible’ whilst painting tobacco control advocates as ‘extremists’ using the “slippery slope” and “nannyism” arguments (“tobacco, then alcohol then red meat and other products”) to weaken credibility (70,71).

Lessons from history

Manipulation of research is, and has been, an important part of the tobacco industry’s campaign against regulation. The true extent of this deception has only been revealed through public release of millions of confidential tobacco industry documents following US law suits. The main goal of research manipulation is to generate controversy and cast doubt about the health risks of smoking and tobacco. Bero details the strategies used to “deny, downplay, distort and dismiss” the evidence on the health effects of second-hand smoke (72). These strategies included funding and publishing research that supported the industry position; suppressing and criticising research that did not support its position; changing the standards for scientific research; and disseminating interest group data or interpretation of risks via the lay press and directly to policymakers. These same strategies are being used in the debate on ENDS to downplay the risks and accentuate the ‘harm reduction’ angle. As the prevalence of tobacco smoking appears to be decreasing in most high-income countries and stabilizing in the WHO African and East Mediterranean regions, tobacco companies are diversifying with ‘lower health risk’ marketed products. ENDS, including heat-not-burn devices, represent a huge potential for tobacco companies with an estimated global market value of USD18 billion in 2017 (73) and 35 million regular dual or sole users in 2015 (74), although still dwarfed by combustible tobacco cigarettes [nearly USD700 billion in 2017, excluding China (73)].

The ENDS market is now dominated by transnational tobacco companies who have acquired smaller independent companies and released their own products. During this transition period aggressive marketing using established ploys learned from cigarette marketing and heavy investment [increase in advertising spend from $12 million in 2011 to $125 million in 2014 (75)] have propelled the surge in ENDS use. Marketing tactics include extensive advertising on the Internet, in mainstream media, at point-of-sale, and product placement, television commercials, and direct-to-consumer marketing via web-sites and social media. Use of flavourings, banned in cigarettes, is an important marketing technique designed to appeal to children and adolescents (76) and e-cigarettes are now the most popular tobacco product amongst youth. In December 2018, Altria purchased a 35% share of e-cigarette manufacturer JUUL for US $12.8 billion. Since its launch in mid-2015, JUUL has grown to become the market leader in the US, comprising 75% of the US e-cigarette market and, through innovative, targeted social media, the most popular device amongst children (77,78).

It is clear that the tobacco industry is targeting children (new users) through its marketing, yet opportunistically cites ‘harm reduction’ as an advantage of ENDS (79). As stated by PMIs’ CEO, PMI’s vision for a smoke-free future, is one in which consumers switch from combustible cigarettes to “reduced risk products” such as heated tobacco products (80). Contemporary evidence of industry funded research and selective reporting was illustrated in PMI’s application to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for modified risk tobacco product (MRTP) status for the IQOS heat not burn product. A Reuters investigation found shortcomings in the training, professionalism and knowledge of some of the principal investigators responsible for five clinical trials submitted to the FDA (81). The FDA rejected the application in January 2018, indeed subsequent examination of PMI data showed more, rather than less, harm (82,83). Regardless, IQOS is already available in over 30 countries. Biased research funded by industry remains prolific in the ENDS arena; a systematic review of the relationship between industry links and study outcomes found very high odds (OR 91.50) of studies finding of ‘no harm’ when the industry conflict of interest (COI) was strong or moderate compared to studies with absent or weak industry COI. Almost all papers without a COI found potentially harmful effects of e-cigarettes whereas only 7.7% of tobacco industry-related studies found potential harm (84).

The industry continues to fund pro-vaping opinion, for example, ‘moderate’ doctors misreporting evidence (85,86), reaffirming their ‘divide and conquer’ strategy again in 2014 (58), lobbying groups, sham supportive campaigns and front groups coordinated by tobacco companies particularly in economically wealthy countries with falling cigarette consumption (63,87,88), whilst at the same time continuing to aggressively market cigarettes in Africa and Asia (89).

Conclusions

Overall, the ENDS agenda set out by the tobacco industry is “disappointingly familiar” (90). The tobacco industry continues its relentless pursuit of profit using well-funded and well-rehearsed strategies. It is applying the lessons learned from 100 years of cigarette marketing and counter-control propaganda to cast doubt, confuse, divide and misdirect e-cigarette regulation, seeking to recruit new generations of smokers and nicotine addicts. Just as with cigarettes, the long-term consequences of regulatory inaction will not become apparent for at least a generation, but by then it will be too late. A proactive and coordinated approach to ENDS regulation is required within the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and should not be delayed.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- WHO | World Health Organization [Internet]. WHO FCTC. [cited 2017 Dec 12]. Available online: http://www.who.int/fctc/cop/en/

- WHO | MPOWER [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2015 Jun 2]. Available online: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/en/

- WHO-FCTC-2018_global_progress_report.pdf [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: https://www.who.int/fctc/reporting/WHO-FCTC-2018_global_progress_report.pdf

- Timeline and international developments - Cancer Council Victoria [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: https://www.cancervic.org.au/plainfacts/timelineandinternationaldevelopments

- 19.10 WHO FCTC in a domestic context: Case study example of Australia’s Tobacco Plain Packaging - Tobacco In Australia [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-19-ftct/19-10-who-fctc-in-a-domestic-context-case-study-example-of-australias-tobacco-plain-packaging/

- JT International SA v Commonwealth of Australia [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: http://eresources.hcourt.gov.au/showCase/2012/HCA/43

- Australia - Certain Measures Concerning Trademarks, Geographical Indications and Other Plain Packaging Requirements Applicable to Tobacco Products and Packaging: Report of the Panel [Internet]. 2018 Jun [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: https://www.wto-ilibrary.org/dispute-settlement/australia-certain-measures-concerning-trademarks-geographical-indications-and-other-plain-packaging-requirements-applicable-to-tobacco-products-and-packaging_16336cac-en

- Investment tribunal dismisses Philip Morris Asia’s challenge to Australia’s plain packaging [Internet]. WHO FCTC Secretariat’s Knowledge Hub on legal challenges. 2016 [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: https://untobaccocontrol.org/kh/legal-challenges/investment-tribunal-dismisses-philip-morris-asias-challenge-australias-plain-packaging/

- Zhou S, Wakefield M. A Global Public Health Victory for Tobacco Plain-Packaging Laws in Australia. JAMA Intern Med 2018;179:137-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hefler M, Editor N. Austria’s new government: a victory for the tobacco industry and public health disaster? [Internet]. Blog - Tobacco Control. 2018 [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/tc/2018/01/09/austrias-new-government-a-victory-for-the-tobacco-industry-and-public-health-disaster/

- Health-Policy-in-Austria-March-2017.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Health-Policy-in-Austria-March-2017.pdf

- YOUNG EAP BLOG MAY 2018: PROTECTING CHILDREN FROM TOBACCO [Internet]. Available online: http://eapaediatrics.eu/newsletter-article/young-eap-blog-may-2018-protecting-children-tobacco/

- Matayoshi T, Tabuchi T, Gohma I, et al. Tobacco and Non-Communicable Diseases Control in Japan. Circ J 2018;82:2941-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsugawa Y, Hashimoto K, Tabuchi T, et al. What can Japan learn from tobacco control in the UK? Lancet 2017;390:933-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feliu A, Filippidis FT, Joossens L, et al. Impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and quit ratios in 27 European Union countries from 2006 to 2014. Tob Control 2019;28:101-9. [PubMed]

- Lombard HL, Doering CR. Classics in oncology. Cancer studies in Massachusetts. 2. Habits, characteristics and environment of individuals with and without cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 1980;30:115-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ochsner A, DeBakey M. Surgical considerations of primary carcinoma of the lung. Surgery 1940;8:992-1023.

- Wynder EL, Graham EA. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma; a study of 684 proved cases. J Am Med Assoc 1950;143:329-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doll R, Hill AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. Br Med J 1950;2:739-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Health USSGAC on S and, General USPHSO of the S. Smoking and Health [Internet]. Public Health Service Publication No. 1103. 1964 [cited 2015 Aug 25]. Available online: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/B/M/Q/

- Samet JM. The Surgeon Generals’ Reports and Respiratory Diseases. From 1964 to 2014. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:141-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- 2.7 Per capita consumption in Australia compared with other countries - Tobacco In Australia [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-2-consumption/2-7-per-capita-consumption-in-australia-compared-w

- WHO | WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2015 Jun 2]. Available online: http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/

- McInerney TF. WHO FCTC and global governance: effects and implications for future global public health instruments. Tob Control 2018. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lopez AD, Collishaw NE, Piha T. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob Control 1994;3:242-7. [Crossref]

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: https://www.smokefreeworld.org/

- Daube M, Moodie R, McKee M. Towards a smoke-free world? Philip Morris International’s new Foundation is not credible. Lancet 2017;390:1722-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koh HK, Geller AC. The Philip Morris International-Funded Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. JAMA 2018;320:131-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hirschhorn N. Another perspective on the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. Lancet 2018;391:25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- E-cigarettes [Internet]. . [cited 2019 Mar 2]. Available online: /resources/policy-advocacy/policy/e-cigarettes/https://www.quit.org.au

- PHE publishes independent expert e-cigarettes evidence review [Internet]. GOV.UK. [cited 2018 Sep 17]. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/phe-publishes-independent-expert-e-cigarettes-evidence-review

- Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, et al. Adolescent Vaping and Nicotine Use in 2017-2018 - U.S. National Estimates. N Engl J Med 2019;380:192-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watkins SL, Glantz SA, Chaffee BW. Association of Noncigarette Tobacco Product Use With Future Cigarette Smoking Among Youth in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013-2015. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172:181-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Office of the Commissioner C for TP. Press Announcements - Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on proposed new steps to protect youth by preventing access to flavored tobacco products and banning menthol in cigarettes [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 3]. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm625884.htm

- Commissioner O of the. Press Announcements - Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on new enforcement actions and a Youth Tobacco Prevention Plan to stop youth use of, and access to, JUUL and other e-cigarettes [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 3]. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm605432.htm

- Kennedy RD, Awopegba A, León ED, Cohen JE. Global approaches to regulating electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2017;26:440-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Electronic nicotine delivery systems: Report by WHO [Internet]. FCTC; 2014. Available online: http://apps.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop6/FCTC_COP6_10-en.pdf?ua=1

- Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. Background Paper on E-cigarettes (Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems). 2013 [cited 2019 Mar 2]; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13p2b72n

- WHO | Tobacco Fact Sheet [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2017 Dec 11]. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/

- Tuberculosis (TB) [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 17]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

- Road traffic injuries [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 17]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries

- HIV/AIDS [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 17]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids

- Fact sheet about Malaria [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 17]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria

- United States v. Philip Morris USA, Inc. Civil Action No. 99-2496 (D.D.C., 2012) [Internet]. Nov 27. Available online: https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/litigation/decisions/us-20121127-u.s.-v.-philip-morris-usa accessed 06/03/2019

- Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A Randomized Trial of E-Cigarettes versus Nicotine-Replacement Therapy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:629-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Tobacco Industry Interference with Tobacco Control [Internet]. 2009. Available online: https://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/industry/interference/en/

- McCambridge J, Daube M, McKee M. Brussels Declaration: a vehicle for the advancement of tobacco and alcohol industry interests at the science/policy interface? Tob Control 2019;28:7-12. [PubMed]

- Kalra A, Bansal P, Wilson D, et al. Part 1: Treaty Blitz - Inside Philip Morris’ campaign to subvert the global anti-smoking treaty [Internet]. 2017. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/pmi-who-fctc/

- McCabe Centre for Law and Cancer. The new Philip Morris-funded Foundation for a Smoke-Free World: independent or not? [Internet]. 2018. Available online: http://untobaccocontrol.org/kh/legal-challenges/new-philip-morris-funded-foundation-smoke-free-world-independent-not/

- Joossens L, Gilmore AB, Stoklosa M, Ross H. Assessment of the European Union’s illicit trade agreements with the four major Transnational Tobacco Companies. Tob Control 2016;25:254-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Lampe K. The cigarette black market in Germany and in the United Kingdom. J Financ Crime 2006;13:235-54. [Crossref]

- Smith KE, Fooks G, Collin J, Weishaar H, Mandal S, Gilmore AB. “Working the system”--British American tobacco’s influence on the European union treaty and its implications for policy: an analysis of internal tobacco industry documents. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fooks GJ, Peeters S, Evans-Reeves K. Illicit trade, tobacco industry-funded studies and policy influence in the EU and UK. Tob Control 2014;23:81-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leading Case. III. Federal Statutes and Regulations: Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act -- Extraterritoriality -- RJR Nabisco, Inc. v. European Community. Harv Law Rev 2016;130:487-97.

- Aguinaga Bialous S, Shatenstein S. Profits Over People: Tobacco Industry Activities to Market Cigarettes and Undermine Public Health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization, 2002.

- Beare M. Organized corporate criminality – Tobacco smuggling between Canada and the US. Crime Law Soc Change 2002;37:225-43. [Crossref]

- Gilmore AB, Gallagher AW, Rowell A. Tobacco industry’s elaborate attempts to control a global track and trace system and fundamentally undermine the Illicit Trade Protocol. Tob Control 2019;28:127-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- PMI. 10-year corporate affairs objectives and strategies. 2014; Available online: https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/4333395-10-Year-Corporate-Affairs-Objectives-and.html

- McCabe Centre for Law and Cancer. Australia’s plain packaging laws at the WTO: progress to date [Internet]. 2017. Available online: https://untobaccocontrol.org/kh/legal-challenges/australias-plain-packaging-laws-wto/

- Tactics tobacco. Good Quotes on Plain Packaging [Internet]. 2015. Available online: http://www.tobaccotactics.org/index.php?title=Good_Quotes_on_Plain_Packaging

- Physicians for Smoke-Free Canada. Packaging Phoney Intellectual Property Claims. 2009. Available online: http://www.tobaccolabels.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Physicians-for-a-Smoke-Free-Canada-Packaging-phoney-intellectual-property-claims-2009.pdf

- National Preventative Health Taskforce. Australia: the healthiest country by 2020. Discussion paper. [Internet]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2008. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2008/10/apo-nid940-1167226.pdf

- Gartrell A. Exposed: big tobacco’s behind-the-scenes “astroturf” campaign to change vaping laws. Sydney Morning Herald [Internet]. 2017; Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/exposed-big-tobaccos-behindthescenes-astroturf-campaign-to-change-vaping-laws-20170712-gx9lsl.html

- Daube M, Eastwood P, Mishima M, et al. Tobacco plain packaging: The Australian experience. Respirology 2015;20:1001-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freeman B. Making the Case for Canada to Join the Tobacco Plain Packaging Revolution. QUT Law Rev 2017;17:83-101. [Crossref]

- McCabe Centre for Law and Cancer. An initial overview of the WTO panel decision in Australia – Plain Packaging [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://untobaccocontrol.org/kh/legal-challenges/initial-overview-wto-panel-decision-australia-plain-packaging/

- Kelsey J. Regulatory Chill: Learnings From New Zealand’s Plain Packaging Tobacco Law. QUT Law Rev 2017;17:21-45. [Crossref]

- O’Dowd A. Latest legal challenge to tobacco plain packaging is rejected by the World Trade Organization. BMJ 2018;361:k2878. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dyer C. Plain tobacco packaging: release of UK court documents will help other countries, says charity. BMJ 2019;364:l392. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- tactics tobacco. Project Sunrise. 2017; Available online: http://www.tobaccotactics.org/index.php/Project_Sunrise

- McDaniel PA, Smith EA, Malone RE. Philip Morris’s Project Sunrise: weakening tobacco control by working with it. Tob Control 2006;15:215-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bero LA. Tobacco industry manipulation of research. Available online: http://orbit.dtu.dk/en/publications/late-lessons-from-early-warnings-science-precaution-innovation(6eb116db-4a8c-4b22-abef-ce5905cd88b7)/export.html

- British American Tobacco - The global market [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 17]. Available online: https://www.bat.com/group/sites/UK__9D9KCY.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO9DCKFM

- Euromonitor. Global Tobacco: Key Findings Part II: Vapour Products. 2017; Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/global-tobacco-key-findings-part-ii-vapour-products/report

- Office of the Surgeon General. E-Cigarette use among youth and young adults. A report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016.

- Ferkol TW, Farber HJ, Grutta SL, et al. Electronic cigarette use in youths: a position statement of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies. Eur Respir J 2018;51:1800278. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, et al. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control 2019;28:146-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tactics tobacco. E-Cigarettes: Altria [Internet]. 2019. Available online: http://tobaccotactics.org/index.php?title=E-Cigarettes:_Altria

- Peeters S, Gilmore AB. Understanding the emergence of the tobacco industry’s use of the term tobacco harm reduction in order to inform public health policy. Tob Control 2015;24:182-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calantzopoulos A. Open Response to Letter of 14 September 2017 calling on PMI to stop selling cigarettes. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20171012135320/https:/www.pmi.com/media-center/news/details/Index/open-letter-from-pmi

- Lasseter T, Bansal P, Wilson T, et al. Part 3. Clinical Complications - Scientists describe problems in Philip Morris e-cigarette experiments [Internet]. 2017. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/tobacco-iqos-science/

- Moazed F, Chun L, Matthay MA, et al. Assessment of industry data on pulmonary and immunosuppressive effects of IQOS. Tob Control 2018;27:s20-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chun L, Moazed F, Matthay M, et al. Possible hepatotoxicity of IQOS. Tob Control 2018;27:s39-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pisinger C, Godtfredsen N, Bender AM. A conflict of interest is strongly associated with tobacco industry-favourable results, indicating no harm of e-cigarettes. Prev Med 2019;119:124-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han E. Secret industry funding of doctor-led vaping lobby group laid bare. The Sydney Morning Herald [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/healthcare/secret-industry-funding-of-doctor-led-vaping-lobby-group-laid-bare-20180823-p4zzc5.html

- Swanson M. What does the evidence say: A Rebuttal to Dr Mendelsohn’s blog published on the ATHRA website on 2 December, 2018 [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://www.acosh.org/evidence-say-rebuttal-dr-mendelsohns-blog-published-athra-website-2-december-2018/

- Cox E, Barry RA, Glantz S. E-cigarette Policymaking by Local and State Governments: 2009-2014. Milbank Q 2016;94:520-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knapton S. MPs behind controversial e-cigarette report criticised for vaping lobby links. The Telegraph 2018.

- Drope J, Schluger N, Cahn Z, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. Sixth Edition. 2018; Available online: https://tobaccoatlas.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/TobaccoAtlas_6thEdition_LoRes.pdf

- The Lancet Oncology. E-cigarettes - new product, old tricks. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1543. [Crossref]